Dr David Barrett, Programme Director for the University of Hull's part-time, online MSc in Healthcare Leadership, explores the ongoing debates about the differences between leadership and management.

Within healthcare, there are those that lead, those that manage and those that do a bit of both. Both roles are critical to the delivery of high-quality and effective healthcare, and both have been researched and written about for decades. Nonetheless, there remains ongoing discussion and disagreement about the relationship between leadership and management.

Though it is broadly accepted that leadership and management are different, there is less clarity on exactly how they differ, how they are similar, and how they function together. So, what is the difference between leadership and management, and does it really matter?

Leadership old; management new?

One element of the theoretical discussion of leadership vs. management is the view that the former has been in existence for centuries, whereas the latter is a relatively new phenomenon. John Kotter - one of the foremost authorities on leadership - suggests that “Leadership is an ageless topic. That which we call management is largely a product of the last 100 years” Kotter (1990; p3)

I do have a bit of a problem with this argument. There is no doubt that there have been people identified as ‘leaders’ throughout history – just take your pick of Roman Emperors, Egyptian Pharaohs and Kings or Queens of various countries. There have also been written accounts of what leadership means (and how to be good at it) through the centuries, from Sun Tzu’s ‘Art of War’ (5th Century BC), to Plato’s ‘Republic' (4th Century BC), to Machiavelli's ‘The Prince’ in the 16th Century AD. My concern is more in relation to the argument that management is new…

It’s certainly true that academic focus on the discipline of management is relatively new. It emerged in the form of ‘Taylorism’ – a scientific approach to management which was first published in 1911 by the US engineer FW Taylor. This required ‘managers’ to ensure maximum efficiency within organisations by studying and streamlining the activities of workers, and removing unnecessary tasks.

Taylorism also introduced the concept of performance management, with workers trained to carry out their work at maximum efficiency and follow instructions (and be rewarded with higher pay for doing so) (Melo & Beck, 2014). Taylorism also saw the rise of managers as a recognised part of an organisation's workforce, and a shift in power from those that ‘did’ the work, to those that managed the workers.

Though developed over a century ago – and though out of favour as a standalone theory by the mid-20th Century - there is a direct line between the ideas within Taylorism and the ‘lean’ healthcare processes and performance management frameworks that many healthcare workers experience within their own organisations.

However, though Taylorism may have seen the birth of the (still relatively youthful) field of management theory, I don’t really agree with Kotter (and others) that the functions of management are new.

Leadership alone does not allow you to gather a record of all your country’s assets (as with William I’s ‘Domesday Book’ in the 11th Century), or build a 140M tall pyramid (as in Giza), or maintain a defensive wall between ancient England and Scotland (as with Hadrian’s wall).

Though the vision that underpinned those achievements required leadership, it needed ‘managers’ (even if they weren’t called that) to oversee the collection of survey data in 1086, to procure supplies to build the great pyramid, and to organise sentry duty on Hadrian’s wall. Like leadership, management has also been around for centuries – we just didn’t call it management.

Why study healthcare leadership? Dr David Barrett explains why it's important:

‘Enormous and crucial’ differences between leadership and management

Putting aside the question of leadership being old and management being new, many theorists have identified what they see as fundamental differences between the actions of leaders and managers. For example, Kotter (1990) outlines how management tasks are designed to bring about consistency and order (involving tasks such as planning and budgeting), whilst leadership should lead to movement and change in an organisation (and encompasses roles such as motivating and inspiring people).

One of Kotter’s contemporaries - Walter Bennis - articulated the core differences between leaders and managers. He outlined that leaders ‘conquer’ the context that conspires against them, whilst managers ‘surrender’ to it. He also provided a list of 12 other what he called “…enormous and crucial” differences as he perceived them (Bennis, 1989; p7). The list includes the suggestion that managers administer and leaders innovate; that managers imitate and leaders originate; that managers accept the status quo and leaders challenge it.

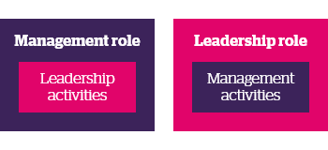

This suggests that leaders and managers should be seen as entirely separate roles – something referred to by Simonet and Tett (2013) as ‘bidimensionality’ (see figures below), and perhaps best summed up by Abraham Zaleznik who – in his classic 1977 paper on this topic – stated that “managers and leaders are very different kinds of people. They differ in motivation, personal history and in how they think and act.”

From a healthcare perspective, the World Health Organisation (2007) provides a brief insight into where leadership and management differ. They highlight that whilst healthcare leaders set the strategic vision and mobilise the efforts towards its realisation, good healthcare managers ensure effective organisation and utilisation of resources to achieve results and meet the objectives. This aligns quite closely with the views of theorists such as Kotter, Bennis and Zaleznik in relation to the differences between leaders and managers more generally.

In practical terms then, whereas healthcare leadership is focused on inspiring, motivating and guiding others towards a vision of safe and effective patient care, healthcare management focuses on the nuts and bolts of organisation and delivery (e.g. efficient utilisation of staff, finances and physical resources; performance management; audit).

Again, I don’t think it’s as clear cut as this. We may all know and work with people (or you may be someone) who you would firmly identify as a leader or a manager. However, would you say that they or you were only a leader, or only a manager? I think we need something a bit more nuanced, which recognises that the two concepts are much more closely linked.

One perspective that might better illustrate the links between leadership and management is described by Simonet and Tett (2013) as the ‘hierarchical’ model, where leadership activities are an important element of those in management roles, and/or vice versa.

In most cases, those who subscribe to the hierarchy model either hold the view that leadership is a subset of management, or that management is a subset of leadership, rather than the two perspectives being interchangeable.

The argument for the ‘leadership-in-management’ model is that leadership is fundamentally about relationships with people, and is therefore an element of a managerial role which involves interactions with all resources, including people.

Conversely, advocates for management-in-leadership highlight that in order to be an effective leader, it is necessary to be able to operationalise a vision (i.e. to manage its implementation) (Simonet and Tett, 2013).

The co-dependency of leadership and management

There will always be discussion and disagreement about the nature of the relationship between leadership and management. However, there is more consensus about the view that in order to be successful, organisations require a combination of effective leadership and management (Algahtani, 2014), whether provided by individuals who wear both ‘hats’, or by separate leaders and managers (or a combination of both models).

Leadership alone may provide organisational vision and build a supportive culture, but it won’t solve the complex operational challenges faced in healthcare every day. Management alone can implement plans to meet organisational objectives, monitor outcomes and utilise resources effectively, but these operational functions need to guided by the clear vision that only a leader can bring.

We can also see how leadership and management are synergistic and complementary at an individual level. Even the most mundane managerial task – writing a staff rota for example – cannot be completed without exhibiting some leadership, whether it be through your team understanding the importance and value of an adequate skill mix, through to instilling a sense of duty and collegiality within the team that encourages a willingness to fit around organisational need.

Does it matter?

So, on the basis that there is substantial overlap between leadership and management, that individuals often perform both roles and that effective organisations need a combination of the two, do the differences matter? Well…to an extent, yes.

I do think that the importance in differentiating between leadership and management is overstated at times. For example, a YouTube video of a highly-respected leadership theorist exists where they describe mixing up leadership and management as “dangerous”. It’s not. Pandemics, sharks and tornados are dangerous; mixing up leadership and management can just be a bit misleading and unhelpful.

Having said that, there is value in knowing where the differences and similarities lie between leadership and management. Understanding the differences can help organisations identify whether they have any weaknesses in one or the other – for example, they may have a clear vision and supportive culture (strong leadership), but struggle with the coordination of day-to-day functions (lacking in management capacity). This in turn can inform their recruitment and staff development activities.

At an individual level, having insight into the differences between leadership and management enables us to frame our own strengths and weaknesses, and focus our professional development accordingly.

Final thoughts

Healthcare continues to face complex and rapidly evolving challenges, including financial constraints, consumer expectations, workforce shortages, an aging population and the continuing impact of COVID-19. Neither management nor leadership alone will be sufficient to meet these challenges – we require the vision, the support and motivation offered by effective leaders, and the organisation, structure and certainty offered by effective managers.

In some cases, these roles will be carried out by the same individuals; in some, there will be separate leaders and managers; in most organisations, we will see a combination of both models. Regardless of how they are structured though, a combination of effective leadership and management is required in order to deliver safe, effective and high-quality patient care.

Join our online MSc in Healthcare Leadership and develop the capabilities required to enhance both your own practice and those of whom you work with. Choose from three start dates a year:

References

Algahtani A (2014) Are Leadership and Management Different? A Review. Journal of Management Policies and Practices 2(3): 71-82

Bennis W (1989) Managing the dream: Leadership in the 21st Century. Journal of Organisational Change Management 2(1): 6-10

Kotter JP (1990) A force for change: How leadership differs from management. New York; Free Press

Simonet DV, Tett RP. (2013) Five Perspectives on the Leadership–Management Relationship: A Competency-Based Evaluation and Integration. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 20(2):199-213.World Health Organization (2007) Building leadership and management capacity in health. Available from: https://www.who.int/management/FrameworkBrochure.pdf?ua=1

Zaleznik A (1992) HBR Classic: Managers and Leaders: Are they different? Harvard Business Review March-April 1992; 1-12 (reprint of 1977 article)